Delta History: a March for LGBT Rights

Video screenshot of One Struggle One Fight marchers as they left Locke in March 2009

Gay activism in California is often associated with cities. But in March 2009, a group of activists took their cause on a march through the rural Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta – not a region known for protest marches or gay activism.

The trek was a five-day walk from San Francisco to Sacramento to call for the repeal of Proposition 8, the gay marriage ban that California voters added to the state Constitution in 2008. Organized by One Struggle One Fight, the march went through Walnut Creek, Antioch, Isleton, Locke, and Elk Grove before finishing at the steps of the state Capitol.

Three of the Delta’s five main counties voted in favor of Prop 8, so it might not have looked like sympathetic territory. But march co-leader Seth Fowler said that was part of the point.

“One Struggle One Fight was about direct action and talking to people. There was a really big urban/rural divide, and the question was, ‘How do we make queer people real to people who are mostly just interacting with headlines about us?’”

One answer: by walking through their towns.

He said there were times on the march when he could sense discomfort among people they interacted with.

But there were also many warm welcomes. What the 30 or so marchers were doing “is such important work” the Rev. Christy Parks-Ramage told them when they gathered at the First Congregational Church of Antioch. “And it’s work that we as a congregation have struggled with.”

The church had recently become “open and affirming,” officially welcoming LGBT people in its ministry. The decision caused a split, and so many congregants had left that the church was selling its building to forge a new path.

The marchers also found welcome in the tiny town of Locke, with a population hovering around 70. Locke was built by Chinese immigrants in 1915, two years after the state passed a law forbidding land ownership or long-term leases by non-citizens, so they couldn’t own the land they built on. (So-called Alien Land Laws were invalidated by the California Supreme Court in 1952.)

In an email to fellow organizers, Fowler described his advance visit to Locke, where he met with the Locke Foundation and discussed the march going through the town. “They were receptive and excited at the prospects of becoming the Gayest Town in America, if only for an evening,” he wrote.

The wooden statue of Guanyin, bodhisattva of compassion, now lives in the Locke home of Deborah Mendel and Russell Ooms (not pictured).

When marchers spent the night in Locke, they stayed in a former Baptist church. “There was a really large wooden statue there of Guanyin, the bodhisattva of compassion,” Fowler recalled. “It felt like a very lovely synchronicity to have this being of compassion watch over us as we slept there.”

He reveres Guanyin to this day.

Russell Ooms, who owned the church building at the time, said the group was delightful. “Locke is a quiet town, and suddenly it was filled with energy,” he said. “It was exciting. They were exciting.”

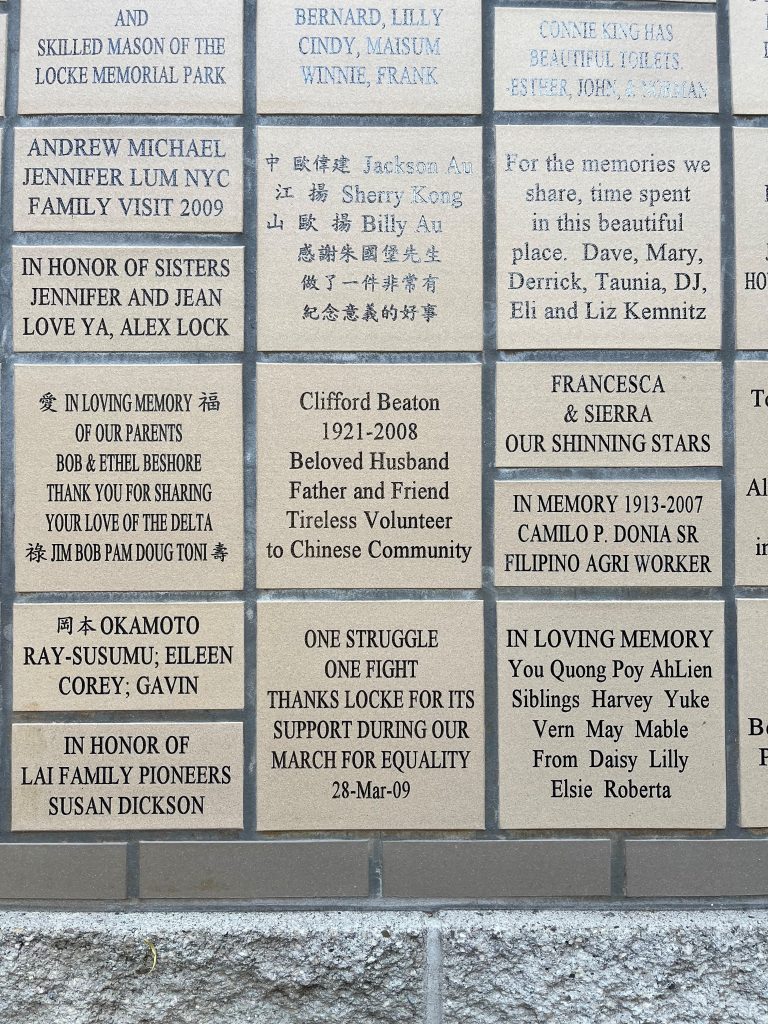

The marchers left behind a gift for the town: a donation to the Locke Foundation, commemorated in a tile that now lives at the Locke Memorial Park. And at least one of the townspeople – Stuart Walthall – joined them at the march’s finale: a rally at the Capitol.

The marchers ultimately got their wish about Proposition 8: It was overturned by the U.S. Supreme Court in 2013. And public opinion in California about gay marriage changed even faster, going from majority opposition in early 2009 to majority support in early 2010.

This year, on Nov. 5, California voters will decide whether to remove Prop 8 language from the state Constitution.

Videos from the march:

- Video from the First Congregational Church of Antioch

- Video from morning in Locke

- Video interview with Connie King in Locke

The marchers made a donation to the Locke Foundation during their stay, commemorated with this tile. (Photo ©Deborah Mendel, used with permission)