Delta Protection Commission Appeals Delta Conveyance Project

WEST SACRAMENTO, Calif. (Nov. 17, 2025) – The Delta Protection Commission voted today to appeal the Department of Water Resources’s certification that the Delta Conveyance Project is consistent with the Delta Plan.

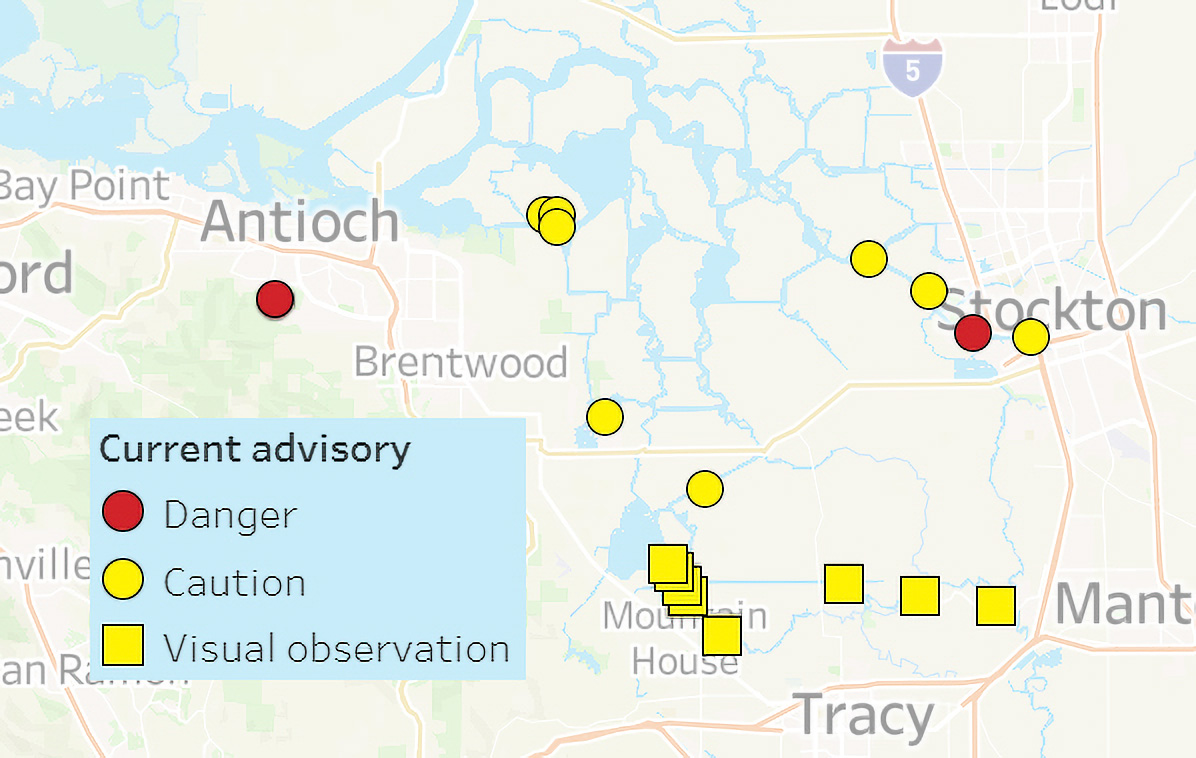

The Project would create a 45-mile tunnel starting on the Sacramento River at the town of Hood and ending at the Bethany Reservoir west of Tracy, near the community of Mountain House in the South Delta.

The Commission’s appeal contends that the Project would do lasting harm to the Delta, irrevocably altering “the rural character of the Delta, its economic pillars (agriculture and recreation), and its cultural heritage.”

It also contends that other options that don’t harm the Delta have not been adequately considered.

The project would use thousands of acres of agricultural land during construction and leave another 1,000 permanently changed, often with industrial-looking facilities, at the four major impact areas: Hood, Twin Cities Road near I-5, Lower Roberts Island, and near the Bethany Reservoir State Recreation Area. Other permanent facilities would be built in the Delta on the tunnel route.

The Delta Reform Act of 2009 establishes coequal goals for the Delta of providing a more reliable water supply for California and protecting, restoring, and enhancing the Delta ecosystem. It also states that the coequal goals “shall be achieved in a manner that protects and enhances the unique cultural, recreational, natural resource and agricultural values of the Delta as an evolving place.”

Commissioner Patrick Hume, a Sacramento County Supervisor, said at a preliminary Commission discussion of the matter on Nov. 3: “This body is the the last bastion of support for the Delta as a place. This is really the voice for the flora, the fauna, the farmers, the Flyway, the fisheries, and the economy that the Delta represents.”

The Commission’s vote to appeal on Monday was 9-0, with one abstention.

The Commission is made predominantly of elected representatives in the Delta, with 11 of its 15 members coming from county boards of supervisors, city councils, and local reclamation districts, which are responsible for flood control in the Delta’s low-lying farmland and small communities.

The remaining four members represent state agencies, and they have typically abstained on votes regarding the Delta Conveyance Project.

Commission Chair Diane Burgis, a Contra Costa County Supervisor, did not attend the meeting today and has recused herself from past discussions and votes regarding the Project. Burgis serves on the Delta Stewardship Council, which will hear the Commission’s appeal and any other appeals filed by today’s deadline.

If the Council upholds any of the appeals, the Project could be remanded to DWR to address Delta Plan inconsistencies.

The Commission’s appeal, including maps showing impact areas, can be seen here (PDF).

Delta Happenings – Oct. 23, 2025

Delta Tunnel, New DPC Leader, RV Bridge, Mute Swans, Stripers

NEWS

- Delta Tunnel News

- Amanda Bohl Is New Delta Protection Commission Executive Director

- Science Board Seeks Comments on Delta Subsidence

- Rio Vista Bridge Closure: Nov. 7-10 and 14-17

- Mute Swan Added to List of Nongame Birds

- F&G Commission Declines Slot Limit for Striped Bass

Ongoing: Delta Leadership Program Applications

Community Events: Veterans Ball, Tree Planting

Delta Protection Commission Names Amanda Bohl Executive Director

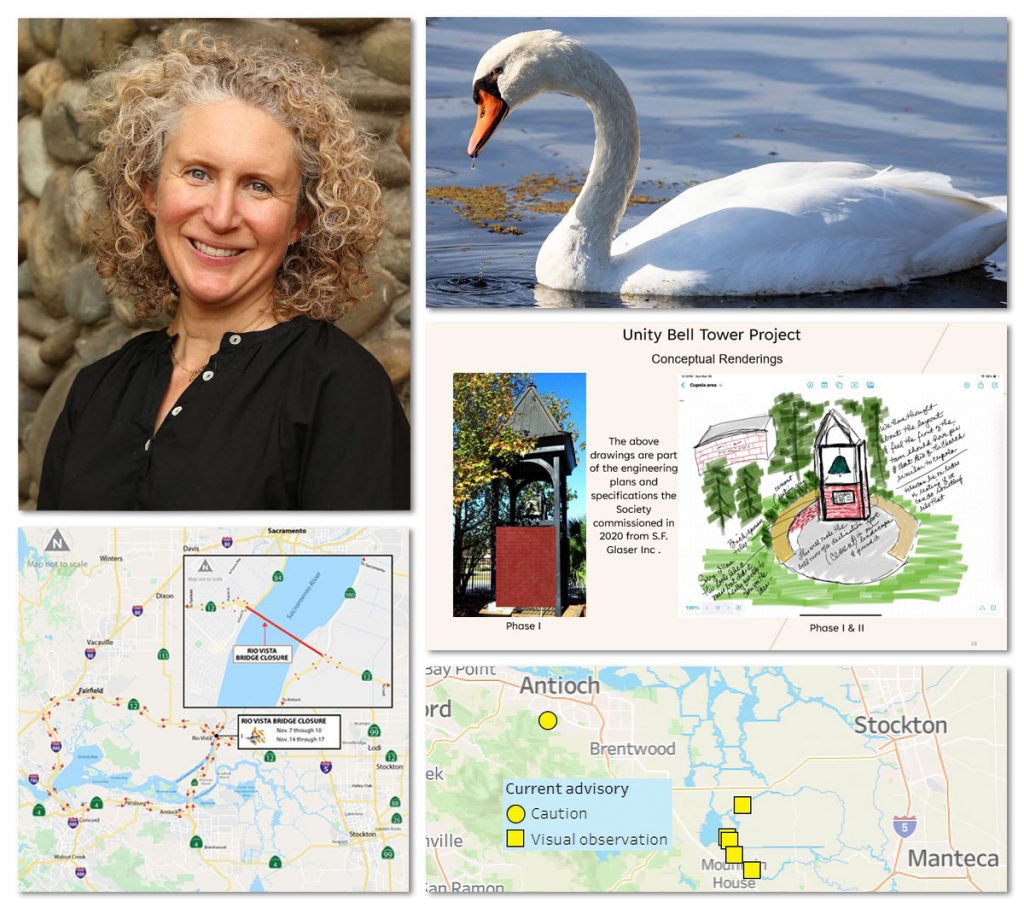

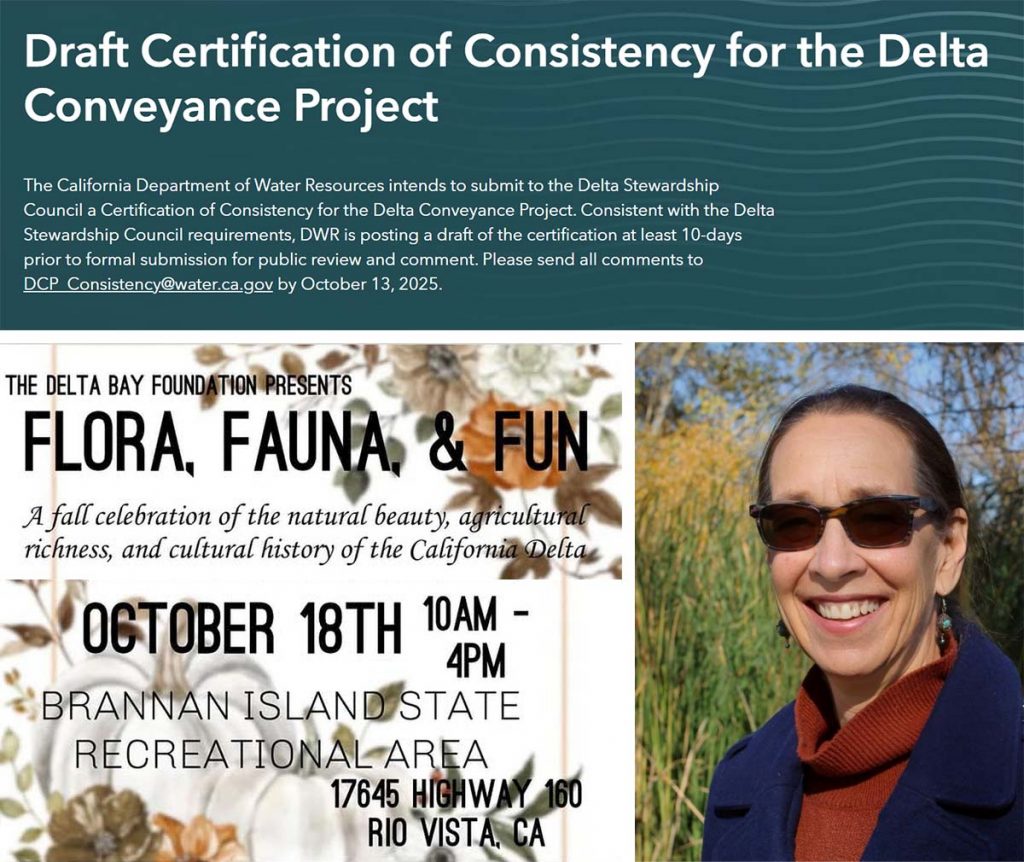

Amanda Bohl

WEST SACRAMENTO, Calif. (Oct. 9, 2025) – The Delta Protection Commission has appointed Amanda Bohl as its next Executive Director. She is expected to join the Commission on Oct. 20.

Bohl currently serves on the executive management team of the Delta Stewardship Council, where she is the Special Assistant for Planning and Science. There, she leads the Delta Plan Interagency Implementation Committee (DPIIC) and guides cooperation among the 18 state and federal agencies – including the Delta Protection Commission – involved in the Delta Plan.

Prior to joining the Council in 2016, Bohl was the Economic Development Lead for the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta Conservancy. There, she managed the Delta Marketing Project and helped develop the Conservancy’s Proposition 1 Grant Program, which funded water quality and ecosystem restoration grants.

“The Delta is one of our greatest treasures, rich in natural resources, agriculture, history, and diverse communities,” said Diane Burgis, Chair of the Delta Protection Commission and Contra Costa County’s District 3 Supervisor.

“We were fortunate to have an outstanding pool of candidates. Moving forward, I’m excited about the Delta Protection Commission’s appointment of Amanda Bohl. She brings the vision, leadership, and understanding needed to navigate the complexities of this unique and vital region.”

Bohl has spent her career focused on people’s connection to the land. “When I think of the Delta Protection Commission, I think of landscapes, the land, places,” she said. “I also think of the best of public service and what government can do to protect places.”

She grew up in Amador County, but her childhood was steeped in Delta life. She enjoyed boating and camping in the Delta with her parents and grandparents, and still remembers the family’s drive to Rio Vista in 1985 to see Humphrey the Whale.

“I’m thrilled to be joining the Delta Protection Commission and to be serving the Delta in this new capacity,” Bohl said. “With new challenges and opportunities on the horizon, the Commission’s mission to protect, maintain, enhance, and enrich the overall quality of the Delta environment and economy has never been more important.”

Bohl has a bachelor’s degree in international studies from Southern Oregon University and a master’s degree in community development from the University of California, Davis. She is a 2014 Water Education Foundation Water Leader, and serves on the board of the Sacramento Valley Conservancy.

Delta Happenings – Oct. 7, 2025

Draft Tunnel Certification, Delta Stewardship Council Appointments, Shoreline Academy

NEWS

- Draft Tunnel Consistency Certification Posted

- Delta Stewardship Council Appointments

- Yolo Basin Foundation Executive Director Steps Down

- Applications Open: Contra Costa Shoreline Leadership Academy

Ongoing: Delta Leadership Program Applications, IEP Workshop Abstracts

Community Events: Oktoberfest(s), Halloween, Two Bell Events

Delta Happenings – Sept. 23, 2025

Antioch Desalination, Sutter Slough Bridge, DPC Interim Director

NEWS

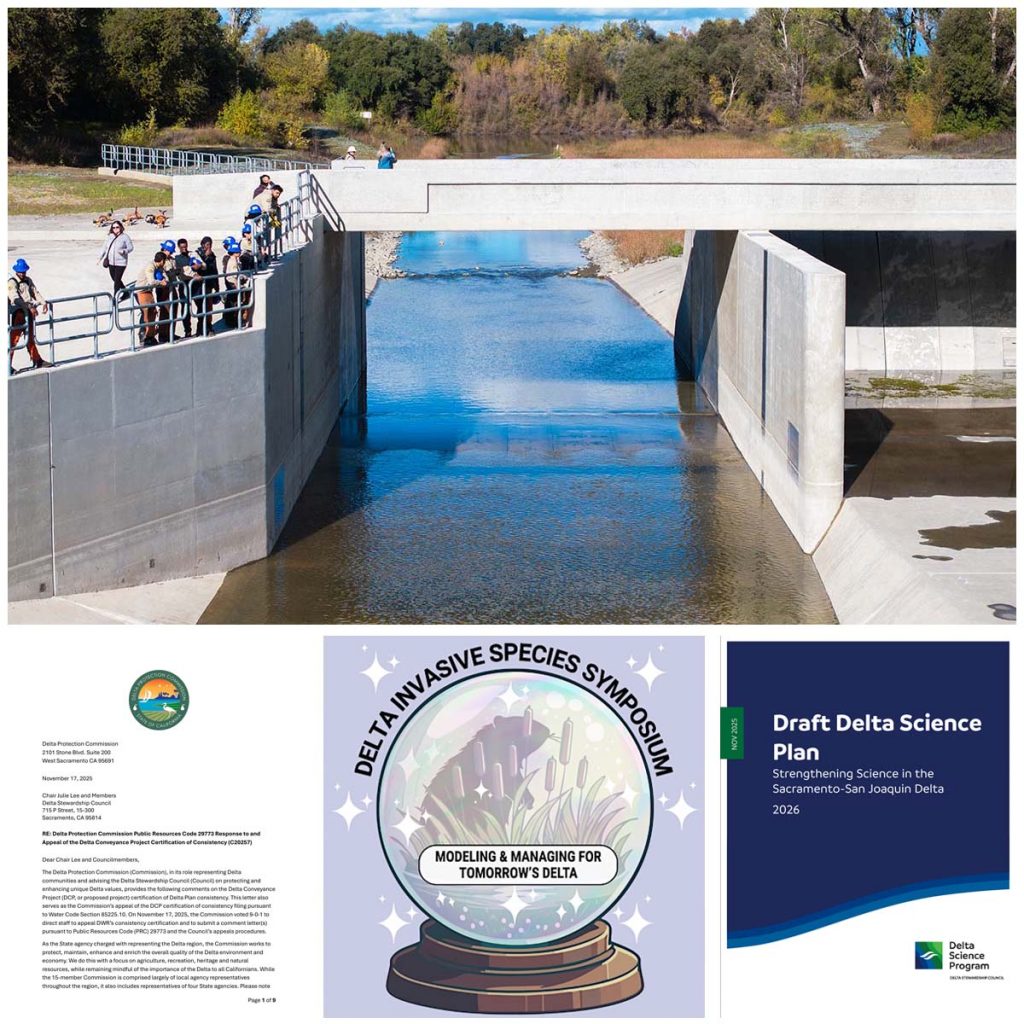

- Antioch Brackish Water Desalination Plant Begins Operation

- Sutter Slough Bridge Closures Through Oct. 10

- DPC Names Interim Executive Director

- WANTED: Delta Leaders

- Caterpillar Exhibit at the Haggin

- Water Board to Reschedule Bay-Delta Plan Workshops, Comment Deadline

Ongoing: Comment Deadlines, Call for Abstracts

Community Events: Rhythms by the River, Oktoberfest, Tractor Fest

Apply for the 2026 Delta Leadership Program (Deadline: extended to Nov. 24)

Applications are open for the 2026 Delta Leadership Program, a joint effort of the Delta Protection Commission and the Delta Leadership Foundation.

Applications are open for the 2026 Delta Leadership Program, a joint effort of the Delta Protection Commission and the Delta Leadership Foundation.

The program targets potential or emerging leaders in the Delta from all walks of life – agriculture, law enforcement, local government, non-profit organizations, local business, and the tourism and hospitality sectors, among others. It puts participants through an intensive curriculum to expand their knowledge of key issues and challenges in the Delta, teach them leadership skills and tools, build relationships and trust, and foster community.

The ultimate goal of the program, which has been operating since 2016, is to build a cadre of dedicated leaders to protect and improve the Delta. Alumni can be seen in leadership positions throughout the Delta and often appear in the news.

What’s Involved

Interested participants can apply through 5 p.m. Monday, Nov. 24, participants are announced the week of Dec. 8, and the curriculum – five day-long seminars held on Fridays – runs January through April. Applicants must commit to 100% attendance on these dates to be considered for participation in the program:

- Seminar 1: Jan. 9, 2026, in Sacramento

- Seminar 2: Jan. 30, 2026, in Stockton

- Seminar 3: Feb. 20, 2026, in Rio Vista

- Seminar 4: March 20, 2026, in Oakley

- Seminar 5: April 17, 2026, in Clarksburg

In addition to attending seminars, participants work on team projects designed to benefit the Delta, with some of the work occurring during seminars and some on their own time – about two hours per month. Participants also can take an air and water tour of the Delta in March or April, date to be determined.

The program concludes with a graduation at the Delta Protection Commission meeting tentatively scheduled for 5 p.m. May 21 at a location in the Delta. The exact date will be determined in November, when Commission sets its 2026 meeting schedule.

Applying

The application form can be completed online. The deadline is 5 p.m. Monday, Nov. 24, 2025.

The quality and content of the application is critical to the applicant’s success. Try to include specific examples and make sure you have included all of your civic and leadership experience and service.

People accepted into the program will be notified by the week of December 8, 2025.

Submission Checklist

- REQUIRED: Complete the Delta Leadership Program 2026 application form online by 5 p.m. Nov. 24.

- REQUIRED: Upload at least one and up to two substantial letters of recommendation. You will upload these during the online application process.

- OPTIONAL: You may upload your resume during the application process.

QUESTIONS?

If you have questions, please contact Program Coordinator Erik Vink at erik.vink@delta.ca.gov or (530) 650-6327.

Delta Happenings – Sept. 9, 2025

Delta Week, Airport Day, Harvest Table(s), Delta Canneries

Ongoing: Bridge Closure, Comment Deadlines, Call for Abstracts

Community Events: Peddlers Faire, Bass Fishing Tournament, Wines of Clarksburg

Delta Heritage Courier – September/October 2025

NHA News, Spooky Tours, and Boozy Nuggets

Read this issue

- Crockett Gets a Shout-Out from Islands Magazine

- National Heritage Area News!

- Anza Expedition 250th Anniversary

- Rio Vista Students Promote Improved Air Quality

- Deer Valley Regional Park to Expand

- Boozy Nuggets

- The City of Brentwood Featured on KTVU

- Benicia’s Sparkly-New Fishing Pier

- Martinez Moves to Revitalize its Waterfront

- Post Card Photographer’s Collection Discovered

ALSO: MUSEUMS, CLASSES and EVENTS

Delta Happenings – Aug. 26, 2025

Tunnel, Rice Partners, Delta Cleanups, Bridge Work, Events, and More

NEWS

- DWR Calls Tunnel ‘Single Most Effective Action for a Sustainable Water Future for California’

- Opposing Viewpoint: Delta Counties Coalition

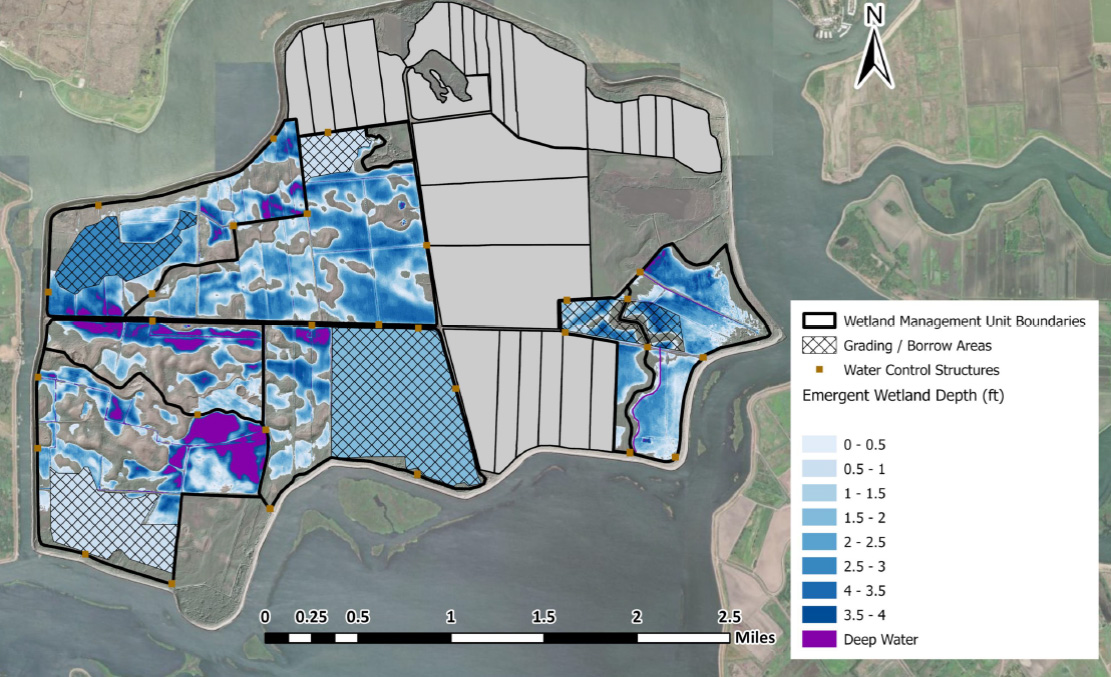

- Rice-Farming Partners Named for Webb Tract, Bacon Island

- Opportunities to Help Clean Delta Waterways

- Delta Stewardship Council Invites Feedback on Public Participation Plan

- Comment Period for Bay-Delta Plan Extended Through Sept. 29

- Interagency Ecological Program Workshop Dates: March 16-18

Ongoing: Bridge Work, Comment Deadlines, Calls for Abstracts

Community Events: Historical Society BBQ, Sip & Stroll, Wines of Clarksburg

Panel (Standout Highlight)

Use .highlight class with .panel-standout for triangle effect. Integer posuere erat a ante venenatis dapibus posuere velit aliquet. Cum sociis natoque penatibus et magnis dis parturient montes, nascetur ridiculus mus. Curabitur blandit tempus porttitor. Integer posuere erat a ante venenatis dapibus posuere velit aliquet. Cras justo odio, dapibus ac facilisis in, egestas eget quam. Aenean eu leo quam. Pellentesque ornare sem lacinia quam venenatis vestibulum.

Panel (Standout)

Integer posuere erat a ante venenatis dapibus posuere velit aliquet. Cum sociis natoque penatibus et magnis dis parturient montes, nascetur ridiculus mus. Curabitur blandit tempus porttitor. Integer posuere erat a ante venenatis dapibus posuere velit aliquet. Cras justo odio, dapibus ac facilisis in, egestas eget quam. Aenean eu leo quam. Pellentesque ornare sem lacinia quam venenatis vestibulum.

Panel (Default)

Integer posuere erat a ante venenatis dapibus posuere velit aliquet. Cum sociis natoque penatibus et magnis dis parturient montes, nascetur ridiculus mus. Curabitur blandit tempus porttitor. Integer posuere erat a ante venenatis dapibus posuere velit aliquet. Cras justo odio, dapibus ac facilisis in, egestas eget quam. Aenean eu leo quam. Pellentesque ornare sem lacinia quam venenatis vestibulum.