Rice: The Other Climate- and Wildlife-Friendly Solution for the Delta

By Holly Heyser

By Holly Heyser

Delta Protection Commission

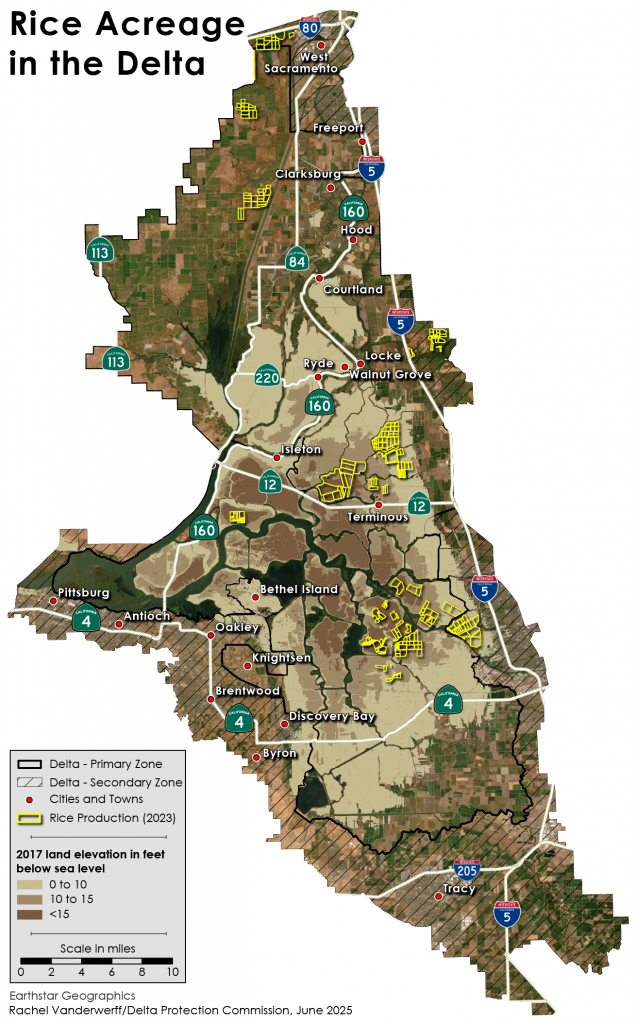

Rice acreage is growing rapidly in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta’s agricultural core.

It nearly tripled in the Delta’s Primary Zone between 2018 and 2022, according to data compiled for the Delta Protection Commission’s March 2025 Socioeconomic Indicators Update (PDF). That took it from the zone’s No. 11 crop to No. 9.

RICE ACREAGE IN THE DELTA (Cropscape data)

| Zone | 2018 | 2022 | Change |

| Primary | 4,808 | 14,095 | 193% |

| Secondary | 1,988 | 3,083 | 55% |

| TOTAL | 6,796 | 17,178 | 153% |

Rice acreage is still dwarfed by corn. At nearly 60,000 acres, corn remained the Primary Zone’s No. 2 crop in 2022. But corn acreage is falling: It dropped 43% in the same period rice was rising.

“We could be looking at 15,000-20,000 acres of rice in the Delta this year,” said Michelle Leinfelder-Miles, Delta Crops Resource Management Advisor for the UC Cooperative Extension.

“I’m learning of rice going in places it hasn’t gone before,” she said. “The Delta community seems really coalesced on developing a rice industry.”

Why Is This Changing?

Both crops grow well in the Delta’s core, where high water tables limit what thrives. So why is rice gaining favor?

One reason is profit.

Staten Island now has 4,500 acres in rice, up from 300 in 2019. “It’s been more profitable than corn, 100%,” said Jerred Dixon, who manages the property as a living laboratory of wildlife-friendly farming for The Nature Conservancy.

“I make really good money growing rice,” said Dixon, who is also a member of the Delta Protection Advisory Committee. “You plant it, you watch it, then you harvest it. It’s not a very labor-intensive crop.”

Jerred Dixon inspects drill-seeded rice on Staten Island during planting in April. Staten has shifted substantial acreage from corn to rice.

It’s also immune to one of the biggest challenges to growing rice farther north in the Sacramento Valley: water availability. The Delta always has water, even in drought. The biggest concern with Delta water is salinity levels.

But another reason for the shifting agricultural mosaic is self-preservation. Corn exacerbates a serious problem: subsidence. Rice doesn’t.

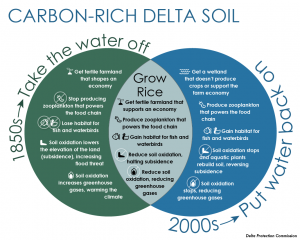

What Is Subsidence?

The organic materials in the Delta’s peat soil oxidize when they hit air, turning into carbon dioxide. The soil disappears; the elevation drops.

After a more than a century of growing dry-soil crops on lands that were drained for farming, islands in the Delta’s core sit as much as 24 feet or more below sea level. That’s a double whammy for levees that sit at sea level.

First, levees are threatened by the sheer pressure of river water that sits higher than the islands, which can lead to levee breaks. Second, that water can also start moving soil particles underneath the levee, leading to a collapse. “That’s what happened on Victoria Island last year,” said Steve Deverel, Principal Hydrologist of HydroFocus.

Both issues elevate the risk of floods that can turn farms into an inland sea, permanently.

How Is Rice Better?

Re-wetting the soil stops the oxidation, preventing further subsidence.

There are two ways to re-wet the soil: restoring wetlands or converting to flooded crops like rice.

Wetlands actually rebuild the soil, albeit slowly – it could take 150 years to restore elevations on some Delta Islands. But wetlands don’t produce a crop, and convincing a farmer to forego a way of life is a tough sell, at best.

Rice fields aren’t flooded year-round, so they don’t have as much subsidence benefit as permanent wetlands. But rice is a substantial improvement over dry-field farming, and it helps maintain the farm economy and Delta livelihoods.

The Delta Protection Act calls for the preservation of agricultural viability in the Delta. Loss of working farmland can hollow out the critical mass needed for local farm services, leading to a downward spiral in the linchpin of the region’s economy.

Loss of farm revenue brings additional risks: Agricultural revenue pays for levee maintenance in much of the Delta, where myriad reclamation districts were established to reclaim islands from tidewater.

“The overarching benefit (to rice) in my mind is levee stability and water supply reliability,” Deverel said.

Rice planting on Staten Island in April

Where Is State Policy on All of This?

There is a lot of activity aimed at re-wetting soil in the Delta’s most subsided lands, but not just because of subsidence.

While subsidence is a grave local threat, its byproduct is a global one, because carbon dioxide warms the atmosphere. Because of the dynamic with peat soil, the Delta produces 21% of the state’s non-animal farming greenhouse gases, while it is home to only 6% of the state’s plant-based farming.[i]

California has committed to net-zero carbon emissions by 2045, and a recent state law – AB 1757 – requires setting ambitious targets for nature-based solutions. Part of the plan to reach those targets is re-wetting 50,000 of the 150,000 most subsided acres in the Delta[ii], whether with wetlands or rice.

“The 150,000-acre area we’re focused on is highly organic, deeply subsided, and very likely not viable for the future,” said Campbell Ingram, Executive Officer of the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta Conservancy. “It’s the landowner’s choice, but unless they’re re-wetting the soil, they literally are digging that hole deeper every day.”

The Conservancy has awarded more than $34 million in Nature Based Solution grants to restore wetlands and help farmers convert to rice in the Delta. The rice conversion funding will add about 5,500 acres – a substantial increase for the Delta.

Conversion costs are one of the biggest obstacles to growing rice, because rice requires specialized water infrastructure and GPS-leveled land for optimal production.

“The viability of these lands is very much in doubt over the long term,” Ingram said. “What we’re incentivizing is a way to try to keep your land viable.”

A harvested rice field adjacent to a wetland in the Yolo Bypass Wildlife Area (PHOTO: Department of Water Resources)

Another Perk of Rice: (Paid) Wildlife Benefits

Rice in the Sacramento Valley has long been lauded as “surrogate wetlands” for waterbird habitat.

Traditionally in California, rice farmers burned rice straw after the harvest to prepare fields for spring planting, but burning was sharply curtailed in the 1990s to improve air quality in the Central Valley. Many farmers switched to winter flooding to decompose rice straw, providing hundreds of thousands of acres of habitat for waterfowl and shorebirds that migrate here during the winter.

Farmers can monetize this. Flooded rice fields that attract waterfowl can be leased to duck hunters. In addition, the BirdReturns program pays farmers and wetland managers to flood fields to appropriate depths for shorebirds at key times during the migration.

A recent UC Davis study highlights even broader wildlife benefit to keeping a mosaic of rice and wetlands on the landscape. It concluded 500,000 acres of winter-flooded rice is needed in California to support not only the waterbirds, but also sandhill cranes, giant garter snakes (listed as “threatened” on the Endangered Species List), and fish, particularly the endangered winter run chinook salmon.

How Does Rice Help Fish?

The fish benefit stems from rice fields’ unintentional second crop: zooplankton. When you add shallow water to land and keep it flooded for at least three weeks, the dissolved carbon leads to bacterial growth that creates an explosion of small invertebrates collectively called zooplankton. Zooplankton makes great fish food.

Prior to the arrival of modern agriculture – and, importantly, the levees that enable it – fish could often swim freely between river channels and shallow-flooded wetlands, where they grew fat on zooplankton. Levees sever that connection, constraining fish to fast-moving river channels that are fish-food deserts. This is one of many factors contributing to the decline of salmon and other native fish populations.

In the Sacramento Valley, researchers have experimented with connecting waterways to historic off-channel landscapes, which now include winter-flooded rice fields, to allow young salmon access. That premise is a central feature of the “Big Notch” project in the Yolo Bypass. Until recently, Fremont Weir has directed water into the Yolo Bypass only when river levels threaten to flood cities. Now, a notch cut into the weir will allow flooding more frequently to benefit fish.

This process, known as reactivating the floodplain, isn’t feasible in the deeply subsided parts of the Delta, where there’s a 25-foot drop from river to farm fields.

But that’s not the only way to feed fish: Farmers can also pump zooplankton-rich water out of their fields and into fish-bearing waterways. This mimics the effect of winter flooding, which pours zooplankton from shallow wetlands into temporarily connected rivers.

CalTrout has a program that pays landowners to grow “zoop soup” and pump it into canals and rivers during key fish migration times in the winter. Its research is showing fish do indeed get fatter from these releases, even as much as six miles downstream, increasing their chances of surviving long enough to spawn.

Tantalizing new research that studies markers deposited in salmon eyeball lenses suggests salmon that feed on floodplain food have a better chance of reaching adulthood.

The sample sizes have been small, but the results are remarkable: Among fall-run chinook salmon, 9% to 16% headed into the ocean showed markers of having fed from floodplain sources, while 45% to 73% that returned to spawn showed those markers. This suggests “floodplain fatties” have an advantage in the survival game.

“We can have both wildlife abundance and agricultural abundance,” said CalTrout Senior Scientist Jacob Katz. “They don’t have to be at odds.”

What’s needed to enlist farmers’ help rewetting Delta soil to meet climate, land subsidence, and fish and wildlife goals without losing their livelihood and way of life?

Re-wetting the Delta has already begun. Wetland restorations have been concentrated on government-owned lands, where profits aren’t a consideration, as well as on portions of agricultural land that have become unfarmable due to loss of land elevation.

Converting from dry-soil crops to rice, though, requires some assistance because it represents a cultural change from familiar, successful, longstanding farming practices.

Sources we consulted with recommended the following options:

- More grant funding to help with conversion to rice (leveling land, installing specialized water infrastructure). One appropriate new source is funding from Proposition 4, the 2024 voter-approved $10 billion general obligation bond for climate resilience, water, and natural resource management programs.

- More grant funding to support wildlife-friendly practices such as timing flooding to serve migrating shorebirds and waterfowl, and to grow zooplankton and release it as pulses of migrating salmon pass by.

- Grant funding to study alternatives that could optimize rice: “Alternative wetting and drying” involves draining rice fields for short periods at key times during plant growth to reduce the bacteria in the soil that release methane, a greenhouse gas. It trades a small increase in carbon emissions for a more substantial reduction in methane, increasing rice’s net greenhouse gas benefit. It has been studied elsewhere, but needs research to confirm it would work well in the Delta.

- Policy and permitting support to bring rice-growing infrastructure to the Delta. Currently, Delta farmers have to ship their rice to the Sacramento Valley for drying.

- Support and assistance for branding and marketing Delta rice. “The quality of rice that comes from the Delta is superb,” said Staten Island’s Jerred Dixon. “It would be great to have a Delta rice label in the future to showcase all the benefits that come from growing rice in the Delta.”

[i] Solutions for subsidence in the California Delta, USA, an extreme example of organic-soil drainage gone awry; Steven J. Deverel, Sabina Dore, and Curtis Schmutte; 2020

[ii] California’s Nature-Based Solutions (NBS) Climate Targets, Appendix 1 – Methodology (PDF), page 35

People we consulted for this article

Lauren Damon, Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta Conservancy

Steve Deverel, HydroFocus

Jerred Dixon, Staten Island

John Eadie, UC Davis

Campbell Ingram, Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta Conservancy

Jacob Katz, CalTrout

Michelle Leinfelder-Miles, UC Cooperative Extension

Laurel Marcus, Fish Friendly Farming

Josh Martinez, California Department of Water Resources

Russ Ryan, Metropolitan Water District of Southern California

Robert Shortt, UC Berkeley

Articles Exploring Delta Data